This literary genre might not be the one which springs to mind when we think about ancient literature. But what is a novel? What are its characteristics and how does it differ from other forms of literature?

A novel is not a myth – a myth is a traditional story, typically concerning the early history of a people and involving supernatural beings or events, for example, the myth of Prometheus. Nor is it a legend, this is also a traditional story and is regarded as historical but has not been authenticated, for example, the legend of King Arthur. Epic, drama, poetry are written in verse – imaginative purposes –while prose is used for history or philosophy, in other words, the collection of information. What is different about the Greek novels is that they are extended stories, imaginative literature, created in prose.

The ancient novel scholar Nicholas Holzberg states that the Greek novel is “… an entirely fictitious story narrated in prose and ruled in its course by erotic motifs and a series of adventures which mostly take place during a journey and which can be differentiated into a number of specific, fixed patterns. The protagonists or protagonist live(s) in a realistically portrayed world which, even when set by the author in an age long since past, essentially reflects everyday life around the Mediterranean in late Hellenistic and Imperial societies.” (Holzberg, 1995: 26)

Is there anything that compares in the modern world with this genre of ancient literature? Today we are familiar with the works of such popular authors as Agatha Christie, Dan Brown, Stephen King, and Hilary Mantel. The Mills and Boon series has been going for many years, and the Game of Thrones books by George R. R. Martin have transferred to the small screen extremely lucratively. In the modern world we have a choice of ways in which we can consume stories – we can watch movies and TV. Visual consumption continues to change and live broadcast TV seems to be becoming less popular with larger audiences subscribing to platforms like Netflix or Amazon Prime.

Was there an equivalent craving for fictional stories in ancient Greece?

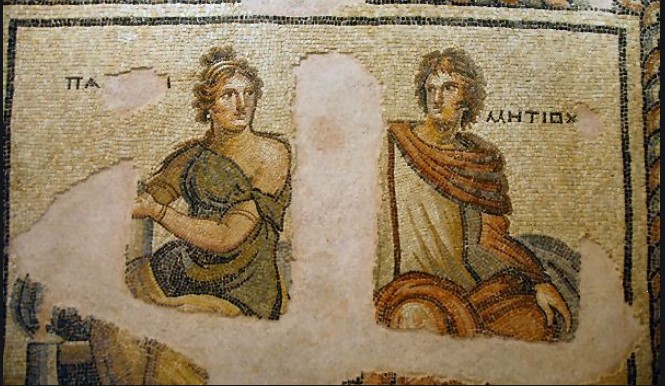

I think the answer must be a resounding ‘yes’. There are many surviving fictional prose texts (for example, early Christian writing or fantastic stories such as Lucian’s True Story). But there are five ancient Greek “novels” or “romances,” which accord with Holzberg’s definition, and which survive almost completely intact. These were written between the first and fourth centuries AD. It’s believed that the novelist Chariton was writing around 50AD (1st century), followed in the 2nd century by Xenophon of Ephesus, Longus and Achilles Tatius, while the latest work, by Heliodorus has been dated to the 4th century AD. Many other novels, which appear to contain some of the same motifs as our five romances, survive in fragmentary form. One of these is Metiochos and Parthenope, and the similarity with Chariton’s Callirhoe has led some scholars to suggest that it may also have been the work of Chariton. Moreover, the characters, Metiochos and Parthenope have been celebrated in a mosaic which was discovered in Antioch.

A large number of other texts could be construed as novels – they are fictional at least. Reardon’s Collected Ancient Greek Novels include Lucian’s True Story which begins with the lines “I will say one thing that is true, and that is that I am a liar … so my readers must not believe a word I say.” It includes journeys to the moon and into the belly of a whale. The Wonders Beyond Thule by Antonius Diogenes is similarly fantastical.

But here, ‘the ancient Greek novel’, refers to five Greek texts from the period of the Roman Empire. These texts are:

- Chariton, Callirhoe

- Xenophon of Ephesus, An Ephesian Story

- Achilles Tatius, Leucippe and Clitophon

- Longus, Daphnis and Chloe

- Heliodorus, An Ethiopian Story

These five novels form a coherent group because of the recurring themes, or motifs, that they share.

- The protagonists are a young man and young girl from distinguished families.

- Both are of comparable beauty, he is incredibly handsome, she is often compared to a goddess.

- They set out on a long journey to far-off lands, either together or separately,

- They undergo a series of harrowing experiences, the most frequent cause of their troubles is their mutual pledge of unswerving fidelity. Frequently in danger of being murdered, and sometimes it appears that they have actually been killed. The protagonists often consider suicide but are saved at the last minute. They can be kidnapped by robbers or pirates, or shipwrecked.

- At the end of their ordeals, the couple are reunited and return home. Chastity, at least in the part of the female, is of crucial importance, and fidelity to one’s partner, together often with trust in the gods, will ultimately guarantee a happy ending.

Where did this genre come from?

Erwin Rohde, a 19th century German scholar who wrote the first major study of the novels, has suggested that the novels were inspired by Hellenistic love poetry. This was the first time that romantic love was treated as a worthy topic of literature. It is possible that the ancient novels have evolved from a number of literary forms: epic, historiography, fantastic travel tales, love poetry, folk stories, drama, rhetoric. It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that the next major work on the ancient novels was written by Ben Edwin Perry, an American philologist. He asserted, in The Ancient Romances: A Literary-Historical Account of their Origins, and with his tongue in his cheek, that “the first romance was deliberately planned and written by an individual author, its inventor. He conceived it on a Tuesday afternoon in July”. But of course a literary genre isn’t invented, rather it evolves. Given the similarity of Heliodorus’ Ethiopian Story to Homer’s Odyssey in structure, and indeed the adventure and romantic elements of the Odyssey, the separation of Odysseus and Penelope and their happy reunion at the conclusion (albeit amongst a bloodbath), we can see the correspondences between the novels and the Homeric epic.

My favourite of the five novels is Callirhoe by Chariton, and in the remainder of this post, I will tell you about Chariton’s novel, and what we know about the author.

What do we know about Chariton?

The first words of Callirhoe are “My name is Chariton, of Aphrodisias, and I am clerk to the lawyer Athenagoras. I am going to tell you the story of a love affair that took place in Syracuse.” (Chariton, Callirhoe 1.1.1). Chariton introduces himself and sets out the purpose of the work. Now compare the opening words of Herodotus’ Histories, “Herodotus of Halicarnassus here displays his inquiry…” and Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War, “Thucydides, an Athenian, wrote the history of the war waged fought between Athens and Sparta.” These eminent 5th century historians also introduce themselves and set out what they wish to achieve in their history. Of the canon of five, only Chariton introduces his novel in this way but this is particularly fitting given that Chariton’s novel is set in the fifth century BC (remember he is writing in the first century AD) and features the historical though anachronistically-chosen characters, Hermocrates, the Sicilian general who defeated the Athenians (you might remember him from Thucydides) and a Persian king named Artaxerxes, possibly inspired by Artaxerxes II, subject of one of Plutarch’s biographies.

Callirhoe – what was it about?

Callirhoe and Chaireas meet in Syracuse on the island of Sicily. It is love at first sight and the two marry. Chaireas’ jealousy is fed by Callirhoe’s disgruntled suitors and he believes her to be unfaithful. He kicks her and she falls unconscious, appearing to be dead. She is buried with a lavish funeral but awakens from her coma inside the tomb, just as pirates are breaking in. Theron, the chief tomb-robber, sells her to the nobleman Dionysius in the Greek city of Miletus, in Asia Minor. He falls in love with her (a recurring theme) but Callirhoe has discovered that she is pregnant with Chaireas’ child so she accepts Dionysius’s marriage proposal to ensure the baby is not born into slavery. Chaireas meanwhile has discovered the empty tomb and he goes searching by sea for Callirhoe’s body. Theron is found, tried and executed. Having discovered from Theron that Callirhoe is alive after all, Chaireas resumes his search, landing in Miletus, but his crew is overcome and Chaireas is enslaved. Callirhoe has let slip to Dionysius that there was a previous husband called Chaireas. Dionysius tells Callirhoe that Chaireas has been killed and he allows her to build a tomb at which to mourn him. Meanwhile Chaireas’ master, Mithridates, has heard of Callirhoe (and has fallen in love with her – see above). Mithridates suggests that Chaireas write to her but the letter is intercepted by Dionysius who accuses Mithridates of attempted adultery and the case is brought before the Persian king. In a dramatic courtroom scene, Chaireas is revealed to be alive after all, and Mithridates is acquitted. The Persian king Artaxerxes has also fallen in love with Callirhoe (here we go again) and attempts to detain her in Babylon by postponing his decision about which man Callirhoe is legally married to. The situation is interrupted by an Egyptian revolt, and Callirhoe is captured. She is presented as a trophy to the Egyptian admiral who turns out to be none other than Chaireas, who had joined the Egyptian army after the revolt, believing that Callrhoe had been returned to Dionysius. Callirhoe surrenders her son to Dionysius, his legal father, and Chaireas and Callirhoe return home to Syracuse to a joyful welcome. (And they live happily ever after.)

Is Chariton’s plot similar to those of the other Greek novels?

Xenophon of Ephesus (An Ephesian Story) is very similar in subject matter to Chariton’s novel. Boy and girl meet at a religious festival, they marry, are separated, one believes the other to be dead, there is a travel and adventure element with pirates, enslavement, and the eventual reunion.

Achilles Tatius (Leucippe and Clitophon) uses ego-narrative (written in first person), altering the reader’s perspective. The couple meet at the beginning of the novel, there are travels and adventures which threaten the chastity of both, pirates/robbers, apparent death, enslavement, and the couple are married at end of novel.

Longus (Daphnis and Chloe) virtually does away with travel and physical adventure, avoiding the separation of his lovers, focussing instead on the psychological development of the protagonists. The boy and girl were adopted by different sets of parents, and they grow up shepherding together. The story deals with their maturation and how they fall in love with one another. Eventually both are reclaimed by their high-status biological parents and marry.

Heliodorus (An Ethopian Story) uses the technique of flashback, borrowed from the Odyssey. We meet a young couple in the midst of their adventure and learn the events leading up to this point through the conversations of the protagonists with the people they meet. Sometimes a flashback within a flashback leads to a very complex story. This novel contains the usual elements: apparent death, robbers, threats to chastity, and even magic and zombies! The story ends with a reunion and a wedding.

How was Chariton’s novel received by his contemporaries?

There are two ancient mentions of a Chariton and Callirhoe. The first is by the Roman satirist, Persius, who lived from 32AD until his early death just 28 years later in 64 AD. He says: his mane edictum, post prandia Callirhoen do (1.134). “To these I recommend ‘What’s on’ in the morning, and Callirhoe after lunch.” Edictum can be translated as “an advertisement for a play” and since Callirhoe was probably published not much earlier, this may refer to Chariton’s novel. Persius is contrasting his own readers with those crude men who were interested only in the latest performances and a frivolous and superficial novel (in Persius’ opinion).

Philostratus meanwhile, is even less complimentary towards Chariton. He writes Χαρίτωνι, Μεμνήσεσθαιτῶν σῶν λόγων οἴει τοὺς Ἕλληνας ἐπειδὰν τελευτήσῃς· οἱ δὲ μηδὲν ὄντες ὁπότε εἰσίν, τίνες ἂν εἶεν ὁπότε οὐκ εἰσίν;

“To Chariton, you think that the Greeks will remember your words when you are dead; but those who are nobodies when they are alive, what will they be when they are dead? (letter 66)

Given that we know so little about Chariton himself, I’d love to think that these quotations might refer to him, although I completely disagree with their sentiments!

What do you think? Would you like to read these ancient novels?

Next time, I will discuss the likely readership of the ancient novels.