One of the most intriguing questions about the ancient Greek novels is who might have read them.

Ben Edwin Perry wrote an influential work on the ancient novels in 1967. He envisaged that in the late Hellenistic period, two forms of literature existed: New Comedy which was aimed at the more intellectual and sophisticated reader, and the other was (in Perry’s words) the “lowly romance of love and adventure, meant for a reading public composed of young or naive people of little education ….”

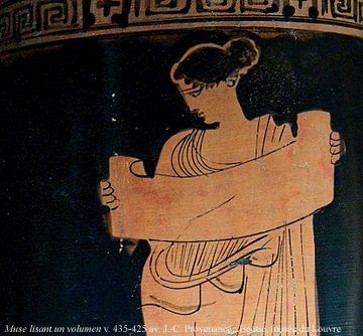

In order to read the ancient Greek novels, one has to be literate. In his book, Ancient Literacy, William Harris suggests that a group he calls ‘semi-literate people’ incorporates those who were literate for a specific purpose, eg., the maintenance of palace records in Mycenae, or slaves who might have learned to read as part of their duties. Women and unskilled workers were unlikely to be literate to any degree and there is no evidence to suggest that the regular instruction for boys was also available for girls in the 5th century BC. But vase paintings clearly show Athenian women holding papyrus rolls, with the implication being that they can read. The scene is of domestic activity which suggests that a woman reading is not an extraordinary pastime.

Plato’s Protagoras states that it was the male children who were educated and attended school, but also that education began in the home, by the nurse, the mother, the tutor and the father himself (325c). According to Plato, this education is the teaching of what is just or unjust, noble or base, holy or unholy, rather than literacy and numeracy which the child will learn at school. While women may have been educated to a limited degree, this was more likely to have happened in the home, for the purpose of either teaching their own sons (and possibly daughters) or it was necessitated by employment.

By the time of the early Roman Empire, the educated male elite were immersing themselves in the written works of Thucydides, Plato and Demosthenes. Meanwhile, the daughters of wealthy families were being educated together with boys in eastern Greek cities such as Teos on the west coast of Asia Minor. An inscription at Teos states that a school employs three teachers to educate boys (παιδες) and girls (παρθενοι). Another inscription at Pergamon, approximately 90 miles north of Teos, shows that girls were awarded prizes in epic, elegiac and lyric poetry, reading and calligraphy.

Chariton’s heroine Callirhoe is πεπαιδευμένη, which means to be educated, or the result of education. The concept of paideia can be translated as educated, cultured, well-bred. It includes other characteristics such as sophrosune (self-control), and the resultant general good character. Callirhoe is γυνὴ πεπαιδευμένη καὶ φρενήρης (6.5.8) (a polite and intelligent woman); Ἑλληνὶς καὶ πεπαιδευμένη (7.6.5) (a cultured Greek lady).

But does πεπαιδευμένη mean that Callirhoe is educated? Chaireas is encouraged by Mithridates to write a letter to Callirhoe (4.4.5), and at no point is there any suggestion that Callirhoe will not be able to read the letter for herself. Mithridates tells Chaireas to “write her a letter. Make her sad, make her happy, make her seek you, make her summon you” (Trans. Goold). Given Callirhoe’s status as the wife of Dionysius, a letter containing the suggestion that she had been unfaithful is rather dangerous. Should the letter fall into the wrong hands (which inevitably it does), Callirhoe’s reputation may be compromised. The letter reminds Callirhoe that Chaireas was her first husband and confirms that Chaireas, whom she was led to believe had died, is in fact very much alive. This information is meant for Callirhoe’s eyes only, and suggests that she does not require someone else, i.e., her husband, to read the letter to her.

Next time, I consider other ways in which the novels could be transmitted.