When I was an Open University student in the 1990s, taking their Classical Greek language module, I found it quite difficult to learn the alphabet without help. Always a book junkie, I took the opportunity to buy some extra textbooks. I read the first pages of each of these, hoping for a magic solution to the brain fog I had over the alphabet.

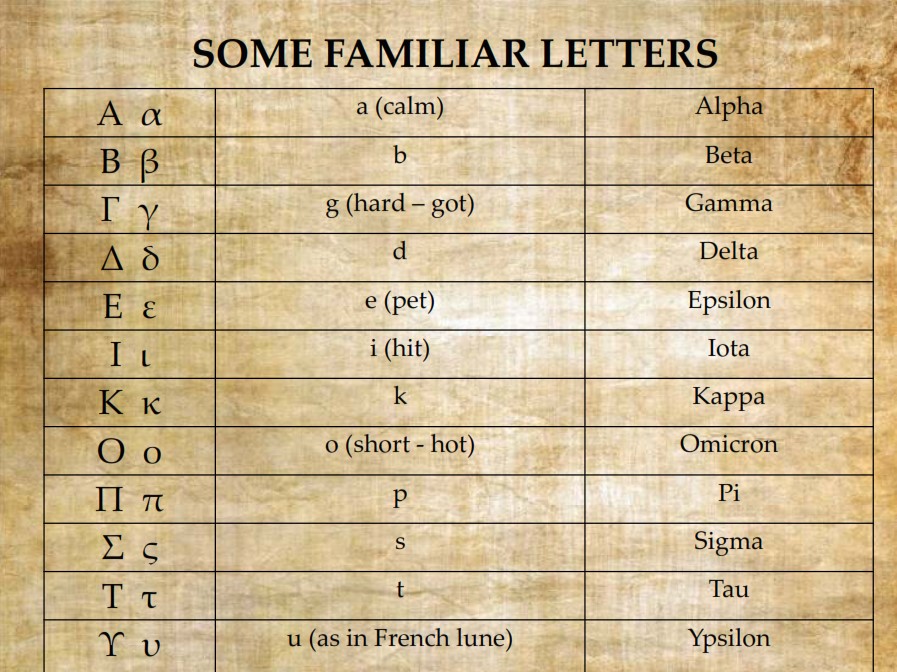

One of the most helpful books I came across was Peter Jones’ Learn Ancient Greek. The chapters had originally formed a newspaper column and Jones takes the student through the alphabet in an informal and friendly manner. He begins with the letters that are familiar to the student and moves on through the less familiar ones. Since this strategy worked well for me, I borrowed this approach for my own students.

Despite the alphabet looking quite daunting (it certainly did to me!), English speakers already know half the Greek alphabet, yes, that’s 12 letters.

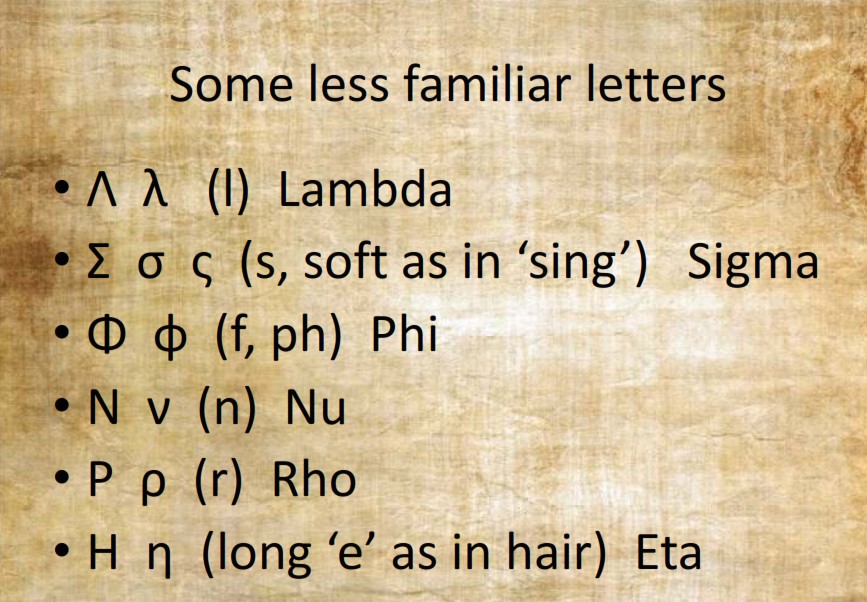

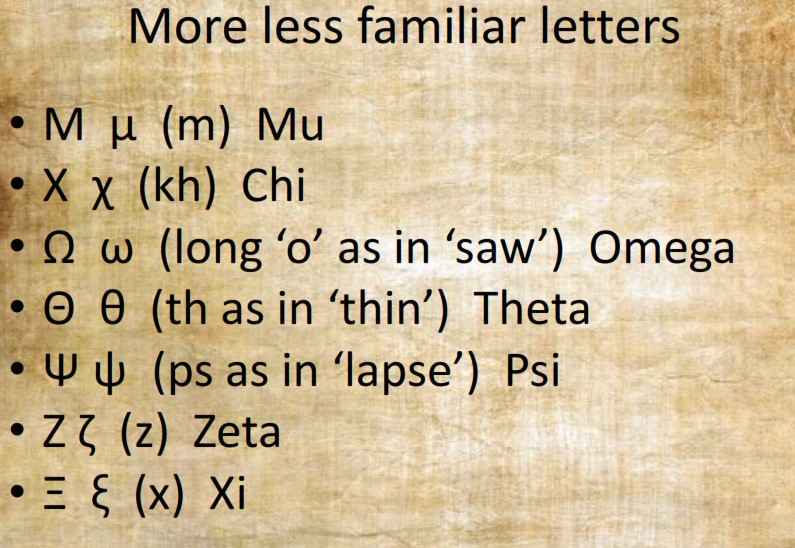

Now though it’s time to look at some letters which look rather different to what we might be used to.

Breathings are important: to omit them or use a breathing incorrectly is a spelling mistake. There is no ‘h’ should in Greek, but if a word begins with a vowel, it must be accompanied by a breathing which indicates the presence or absence of the ‘h’ sound at the beginning of the word.

A smooth breathing indicates absence of the ‘h’ sound, e.g., ἀδελφος, ἐλεφας, Ὀδυσσευς, ἀκουε, ἐστι.

A rough breathing indicates the presence of the ‘h’ sound, e.g., ὁ παις, ἱππος, ἁγιος, οἱ πολλοι, ὁλος, ὁπλα, ὑς.

If the word begins with a diphthong (two letters together which make one sound, see below), the breathing goes over the second vowel, e.g., εἰδος, Οἰδιπους, υἱος.

Diphthongs are two letters which are pronounced as one sound.

- αι as in high παις, δικαι, σπονδαι, αἱ, αἱμα

- αυ as in how γλαυκος, αὐτος, παραυτικα, ταυτα

- ει as in fiancée εἰδος, εἰδη, δειπνον,εἰεν, παυει, εἰη

- ευ (pronounced separately) βασιλευς, Ὀδυσσευς, Ζευς, εὐλογια

- οι as in boy οἰκος, ἀνθρωποι, γενοιτο, οἱ, τοις

- ου as in too ἀκουε, λουω, σου, σοφου, τους, που

- υι (ui) υἱος

- γγ as in finger ἀγγελοι, ἐγγυς, διφθογγος

PRONOUNCIATION

Do we know what ancient Greek sounded like? And if so, how did it sound?

The Attic dialect was that spoken in Attica, the region where Athens is located, in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, and it is in this dialect that much of the surviving literature is written. We can tell how words were pronounced through discussion by ancient grammarians, by spelling mistakes in inscriptions from the fifth and fourth centuries, and from the pronounciation of words which had transferred into, for example, Latin, and we know how Latin was pronounced.

Using this latter method, we can deduce that in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, the letters phi, chi and theta were pronounced ‘p’, ‘k’ and ‘t’. Bearing in mind that Latin had both the letter ‘f’ and the ‘f’ sound, let’s take, for example, the name ‘Daphne’. From the first century AD and onwards, this was spelt in Latin Dafne, implying the Greek, Δαφνη. But earlier than this, the word Δαφνη was spelt Dapne in Latin, suggesting that the φ was pronounced like a hard ‘p’.

In the Speaking Greek CD which accompanies the JACT Reading Greek course, Professor David Langslow suggests the following exercise to distinguish between phi and pi, chi and kappa, and theta and tau: φ, χ, θ (aspirated letters) are pronounced as in pin, kin, tin, while the non-aspirated π, κ, τ are pronounced as in spin, skin and sting. Do you notice the difference? π, κ, τ are much softer. If these letters occur within a word, an English speaker can pronounce them easily as we have seen above with spin, skin and sting. However the difficulty arises when these letters occur at the start of a word, and Langslow offers the solution that π, κ, τ at the start of a word, sound like β, γ, δ.

Of course, Greek was a widespread language with many dialects, spoken in Spain to the west and India to the east, but most prominent in Greece and east Asia Minor (modern Turkey). The suggested pronounciation above was that spoken in Attica during the fifth and fourth centuries BC, but as I have mentioned, by the first century AD, φ, χ, θ were being pronounced as ‘f’, ‘ch’ and ‘th’.

Professors Philomen Probert and David Langslow can be heard reading extracts from the OCR GCSE Classical Greek set texts on the YouTube channel of Classics for All. Click here to listen to Euripides’ Electra lines 215-331.

This has been merely a snapshot into the pronounciation of ancient Greek. While it is interesting to establish as far as possible the authentic pronounciation of the language, it is not necessary to perfect this yourself. After all, as a taxi driver said to me the first time I visited Athens, “who are you going to talk to? Socrates?”

If you are interested in learning more about the ancient Greek language, comment below or contact me on helen@helenmcveigh.co.uk.